To do a postdoc or not to do a postdoc ….

…. That is a question I am asked by many PhD students, whilst postdocs ask me whether they should do another postdoc or leave academia altogether.

The answer, as with many career questions, is not straightforward. The facts show that only a very small percentage of PhD-qualified researchers will eventually go on to secure an academic post. And, even if they do, many of these positions are not permanent in the first instance, and some that are teaching oriented can even come with a zero-hour contract. This is why I spend much of my time helping researchers to transition out of academia into other careers in industry, business and not-for-profit sectors.

However, for the purposes of this blog, let’s take a look at the situation for those researchers who are considering academia as a career option.

If you’re thinking seriously about a career in academia and have aspirations to be a professor, principal investigator or research group leader, don’t just think twice about it, think about it, find out more about it, mull it over and formulate a career strategy. Otherwise, in terms of your career plans, it may well be ‘all academic’ – in other words, nothing you do will change your current situation – it is out of your hands.

I, along with many other career consultants, academics and commentators, have written about careers in academia before and there is a plethora of surveys and research that shows that getting in and getting on in academia is a tough challenge nowadays. This is, in part, due to the burgeoning number of contract researchers ‘on the market’ vs the limited number of available institutional academic posts, as well as the pressures placed on academics to be able to juggle publishing, secure funding, develop an international reputation, manage a research group, teach (including design, delivery, assessment, pastoral care, etc.), review research papers, take on administrative duties, etc. In fact, Susan Wardell (@UnlazySusan on Twitter) created a fantastic infographic that sums up the activities of a university academic very nicely).

Of course, you can avoid some of these responsibilities by joining a research institute instead of a university, where teaching and collegiate duties aren’t part of the job description. Or, alternatively, you can negotiate for a primarily research-focussed role – it all depends on the type of academic position you’re looking for – and you may not get your preferred position to begin with. A recent survey by Nature revealed that the chances of a securing your first academic post can involve at least 15 applications. A now well-established professor I know sent out 60 applications for his first academic position.

This type of resilience is needed for a career that will be challenging in many ways: taking on a leadership role with no prior management or leadership training; being responsible for recruiting and training your own staff and students; the likelihood of being rejected or receiving criticism from your peers, even when you have produced really excellent work.

Due to the high competition to win funding and the pressure to publish in respected international journals, academics are constantly competing with each other to get into the ‘final cut’, which can be a high bar to attain with limitations on available research funds and journal page numbers. So, even if you work 24/7 and produce excellent research, you may not be appreciated by your community, as you might be if you were working in another career sector.

Having said this, many researchers still aspire towards academia as their first career of choice – and, of course, even though the numbers don’t look good, many new academics are employed each year across the world. There is plenty of advice and information to help you to achieve this goal, for example on the Vitae website, but as I pointed out in a recent career workshop, many extra factors and qualities lie under the surface of an academic job vacancy to help you to be successful.

Many of these factors can’t be achieved at the last minute and need to be built up over time, such as networking and forming collaborations, developing a reputation in the field, having research ideas and being able to secure a fellowship or funding, building a record of publications, being resilient and self-motivated. And so on. One thing’s for sure, you will need to move away from promoting your functional and practical expertise that are highly valued as a PhD or early career researcher, and supplant these skills with those related to an academic.

Doing a postdoc can be a smart career move after your PhD, depending on your motivations, but don’t stay too long if you’re not impressed by the future life you see for yourself reflected in the academics around you. And, as soon as you realise you’re unlikely eventually to secure a permanent post, it may be time to think about moving on.

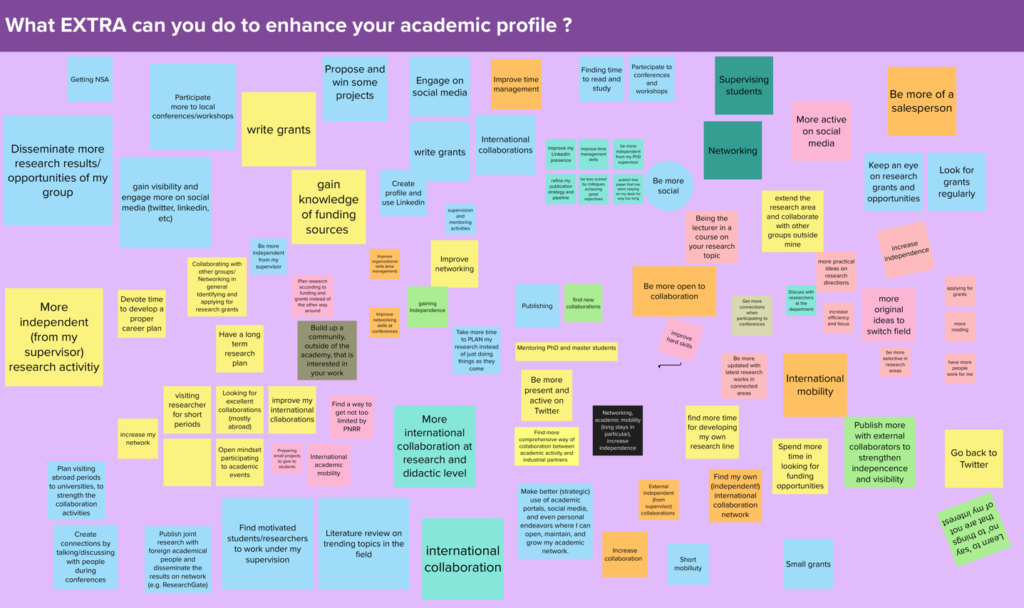

On the other hand, if you like what you see and want to improve your chances of achieving your goal to secure an academic position, take a look at the actions that were identified by researchers of my recent academic career workshop to give you ideas for your career strategy, as well as adding in some of your own.

Wishing you success in whatever you decide to do !

* MURAL Boards created and managed by my workshop digital learning co-partner, Virginie Siret

Related blogs:

What’s the point of a postdoc?

Getting to professor

Many other blogs can be found in my Blog Archive